By Victor Greto

It was the first time I saw my mother cry.

She had come close many times before.

As a child I would see her alone in the kitchen standing over a sink full of dishes — my dad hospitalized again — and notice tears in her eyes.

But this was different. More than 20 years had passed since I left the family home in Ridley Park, Pa.

I had been living in South Florida, and this return visit in June 2002 was to see for myself whether mom needed to be in a nursing home.

She was recovering from a broken wrist in a nearby facility, having fallen while making her bed — a hospital bed, which had been put in the den to help her recuperate from the previous year’s hip operation.

Her recent fall had shown me and my five brothers that, alone in that large house, she needed help.

I took her out of the nursing home for a couple of days to gauge how bad she seemed. Mom’s older sister, Addie, who lived in Plant City, Fla., also made the trip.

One afternoon, we sat around the oak dining room table playing Scrabble.

As we ate crackers and popcorn, Addie talked about a friend whose children recently had put her into a nursing home.

“She told me, ‘They put me in here to die,’” Addie said.

I stared at my tiles. Then I heard Mom sob. Cracker crumbs spewed from her mouth. Tears poured from her eyes.

“Oh, I didn’t mean you, Phil,” Addie said to her sister.

That moment five years ago changed my life, launching me on a personal odyssey to keep my mother, Philomena Greto, out of a nursing home.

The Family Caregiving Alliance reports that more than 50 million people in the United States act as caregivers. About 7 million care for someone older than 65. There are about 83,000 caregivers in Delaware.

From the moment Mom cried, I knew I wanted to come home and take care of her.

****

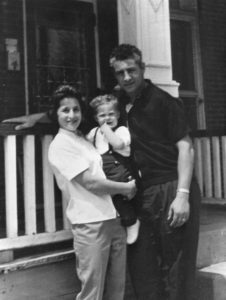

By 2002, my mother’s face had grown tight, paper-thin, bony.

At 73, golden-brown wrinkles etched her still-creamy skin. You could see the hard outline of her skull. She stooped when she walked, loping side to side as she went from the bedroom or living room to the kitchen.

She also had grown bitter.

The pain of recovering from the previous year’s hip operation, coupled with the arthritis that pinched her joints and the Parkinson’s disease that had gripped her body since the mid-1990s, was expressed in a helpless, barely subdued anger.

It was easy to understand.

Before hip surgery, she had convinced herself she was beating the Parkinson’s and arthritis through exercise, medication and a daily dose of cod liver oil.

Cut down by a fall, she could no longer exercise without feeling needle-like, gnawing pain.

I witnessed the debilitating effects of Parkinson’s disease as it damaged the nervous system, balance and mind of a woman who had prided herself on walking and working out to TV exercise programs nearly every day for the past 50 years.

It wasn’t fair, she said to me during that June week.

“I did everything right and this is what I get,” she said. “I don’t deserve this.”

“I’m thinking about leaving her in the home,” my younger brother Jimmy told me soon after that fall. He had taken the lead in caring for both my mom and dad, but had his wife and two children to consider.

I had neither and had done little to help since I left home at 18.

For 20 years, I had stayed away, mostly because of my father.

Not because I didn’t love him; I did.

But long before I was born, my father had been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and manic depression. Every couple of years he would become uncontrollable, and each of my brothers in succession became responsible for taking care of him.

Because of that, I often dreamed of escaping.

I wanted to leave home as early as junior high school, soon after my oldest brother, Sam, who was named after my father, settled in Colorado.

I liked to write the names of the Western states in a copybook: Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Colorado, Arizona — they seemed empty and far away.

One week after I graduated from high school, I moved 1,600 miles to join my brother.

Years passed, and my father’s attacks came closer together. For the final two years of his life, he seemed sick all the time, walking unsteadily through a manic, lithium-inspired haze. I was visiting in January of 2000 when he became ill for the last time.

I watched my dad die from kidney failure, probably caused by years of heavy medication. He lay crumpled on a hospital bed gasping for air.

While Jimmy and Mom sat near, I stood in the doorway, half in and half out, watching and waiting, something it seemed I had done my whole life.

When dad stopped breathing, the 20 years of separation began to dissolve: I suddenly could forgive everything, from the adolescent hatred I felt toward the teasing and taunting of my childhood, to my dad’s sickness, which wasn’t his fault, no matter how it felt.

***

Two years later, when my mother’s condition worsened, returning home became a possibility. I didn’t think my mother needed a nursing home, and I didn’t want her there.

The home was institutional; it reeked of despair; and my mother was just one of many older people sequestered in a series of look-alike cubbyholes, three beds each.

The other patients, mostly women, got around in wheelchairs or were bed-ridden. Many of them seemed to be like Aunt Addie’s friend — waiting to die. With a firm grip on her walker, Mom visited them to cheer them up.

To move back to a place from which you ran away is complicated — there are dozens of ghosts, not just of people, but of incidents, holidays and the strong echo of my own anger.

I pictured myself blocking the front door, trying to stop my old man from leaving the house during one of his attacks. I watched myself running up the stairs to my room to hide under the covers, blocking out the light, the sounds, my thoughts.

To move back home also is as simple as it gets.

I returned with my girlfriend, with whom I had lived for years. Although nervous because neither of us had a job, we were sure it was the right thing to do. We figured it wouldn’t last much longer than a year.

We made a deal: The first person who got a job would support us, and the other would bear the brunt of Mom’s care.

But with Mom, I never drew a timeline. We agreed that she would go into a nursing home when she couldn’t take care of herself in the bathroom.

At first, an avalanche of details consumed us: We talked with a social worker about how to coordinate Mom’s services. Most of them were paid for by a county agency, which orchestrated a labyrinth of federal, state and local assistance that included Medicaid and Medicare.

We discovered that Mom’s teeth were rotting; her rigidly timed medications seemed administered irregularly (she was at times hyperkinetic, at times sleepy); she needed therapy on her wrist, but also therapy on her neck to ease painful spasms that made her scream.

Parkinson’s disease, a degenerative disorder with no known cause and no cure, cripples the central nervous system. About a million people have it in the United States — more people than those with multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy and Lou Gehrig’s disease combined.

The disease pummeled Mom for five years before I came home. It progressively froze her movements and debilitated her memory.

My girlfriend and I had three of Mom’s teeth pulled, paid for new dentures, adjusted her pill regimen, and took her to a physical therapist three times a week.

And we transformed the family home into ours, with our furniture and pictures and books. We put down new rugs, took down heavy curtains to let the sun in, painted kitchen cabinets and installed a new floor.

We moved my parents’ furniture out of their bedroom and put it in an upstairs room, moving in my bedroom furniture, so we could sleep within earshot of Mom.

That was the easy part.

****

I learned a lot about Mom I didn’t know.

The last of seven children, my mother was born in 1929, the year the Great Depression began. Less than two years later, her mother died and her father lost his job; he was in danger of losing the family home in Crum Lynne, Pa., near Chester.

Unable to pay the mortgage, Mom’s father put his children — five girls and two boys — in a Catholic orphanage in Philadelphia. Eventually he found work with the federal Works Progress Administration and finagled a government loan to keep the house.

But my grandfather never made what he earned during the mid-1920s, and his children remained in orphanages or homes until they came of age.

Knowing this helped me understand Mom’s view of the world and her fierce longing for home and family.

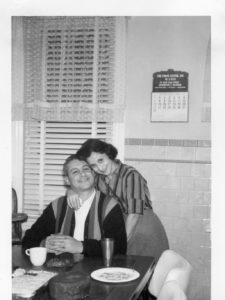

By the time my mother returned to her father’s house, at 14, she was ripe for my dad, whose family lived catty-corner to her home. A romantic who believed in Hollywood endings, she was thrilled by my dad’s athletic exploits in baseball, football and basketball. She fell quick and hard.

She married him, not knowing his condition. She learned to endure.

She wasn’t as willing to suppress her feelings after my return.

The chemistry between my mother and girlfriend proved toxic. It grew worse after I got a job as a reporter at The News Journal.

Mom grated on her, and she grated on Mom. Even though it was my girlfriend who poured the foundation of care my mom received, they bickered constantly.

It was my girlfriend who found Mom a day care, which freed my girlfriend to attend college and eventually find work at a nonprofit.

But by the end of the second year, my girlfriend told me she could not live in the same house with Mom.

One night while I was at work, my girlfriend called to tell me Mom refused to thank her for making dinner and would not speak to her.

And then she handed the phone to my mom.

“What’s going on?” I asked her.

“Oh, Victor,” Mom said in a chilling, uncompromising tone. “I don’t know what to say.”

Neither did I.

By the end of 2005, my girlfriend moved out of the house, and I began to care for Mom alone.

****

I’d heard the sound before, sudden and distinctive, as frightening as squealing brakes.

But the sound of my mother falling was like no other: a solid Bam! followed by the floor’s jouncing echo and my stomach dropping.

I’d heard her fall several times. Usually she fell on her butt. Once she braced herself during a fall with her left hand, and the diamond on her wedding ring cut into the web of her finger. She needed stitches. After that, I made her take off the ring.

When I heard her fall one morning last November, I was getting out of the shower. I left her eating breakfast at the kitchen table and cautioned her not to get up. She had been more unsteady lately, and I always worried she might fall.

She had gotten up without her walker and was making her way to the sink when she fell.

I found her on her left side, her arm tucked beneath her body. Like a child, she looked up at me as if she were ashamed. What I saw was our future: I couldn’t keep her safe.

Until that moment, I had resigned myself to life with Mom, even thought of it as normal.

It was an inflexible routine interspersed with good times: Some evenings, my older brother Perry would visit to play guitar. My youngest brother, David, might bring his newborn daughter to show Mom how big she was getting. On the weekends, Mom and I liked to watch black and white movies.

During good weather, my brothers and I would sit on the front porch talking and smoking cigars. Sometimes after I put Mom to bed, we went out and drank and laughed until we nearly cried.

That July, I held a 77th birthday party for Mom and invited everyone who routinely checked on her. People came from all over: Addie from Florida, Sam from Colorado, and many of her friends whom she hadn’t seen for years.

****

M y relationship with my family peaked at the party, but it also revealed the valley in which I’d lived for months. I had grown increasingly impatient and frustrated.

Although I didn’t realize it, I had caregiver burnout. I was riven with stress, guilt and anger.

I didn’t think it had to do with the ritual of waking Mom, hoping the bed was dry, and giving her pills and apple juice.

Nor did I think it was about getting her safely ensconced in the bathroom.

I didn’t even think it was that she no longer could be trusted alone. Her debilitating disease, her increasingly foggy mind and her own frustration expressed itself in erratic movement.

She had to get up. And that damn walker inhibited her.

So she would leave it and invite disaster.

I insisted to anyone who asked that the greatest stress was the driving: several traffic-heavy miles to the day care center in the morning, then the longer trek to work, followed by the pressure of getting my assignments done before I had to get back on the traffic-heavy road to pick her up before the center closed.

At home, I put her into bed for a much-needed nap, and I finally could do something for myself. Read. Sit on the front porch. Take a walk.

But I couldn’t let her sleep too long because, after dinner, she had to be in bed by 9 p.m.

All the while her pills had to be divvied and swallowed, and bathroom breaks monitored. Getting her teeth cleaned and pajamas on took at least an hour.

And Mom wasn’t always accommodating. As time passed, she became more childlike, refusing to clean her dentures and wanting to stay up later, even though she knew she’d have a hard time waking in the morning.

Once a month, to give me a break, one of my brothers would take Mom for a day. Every year, for the first three years, they also traded off caring for her for a week or two so I could take a vacation.

I felt guilty for leaving her and guilty for getting my brothers involved. So last year I used “respite care,” a program in which a nursing home took Mom for a few weeks.

When I first used it, I didn’t know what to do with all the time I had when I didn’t have to administer pills, watch her, wait outside the bathroom door, put her to bed and listen for her in the night.

While visiting a friend in Boston on a long weekend, I reverted to my childhood. I ate so much pepperoni and so many cashews the first night that I became ill and stayed in bed for two days. I remember looking out from under the covers of my hotel bed at the slivers of sunlight cutting through the heavy curtains and never wanting to get up again.

This was one of many things I did wrong as a caregiver. I also didn’t attend support groups. I occasionally drank too much. I did not “journal” or express my frustration. I rarely spoke to anyone about how I felt.

My brothers and I just didn’t do that. Growing up, we had learned to make fun of anything too serious.

I blushed when some relatives called me “a saint” for taking care of Mom. It was too easy a thing for them to say, and I felt like I could never do enough.

The stress took its toll. When Mom’s prescriptions moved from Medicaid to Medicare, it took months to straighten them out. During one call, I nearly cried in frustration after talking with a clerk. The problem was resolved only after I screamed at her and demanded her supervisor.

I didn’t think I was stressed even after, another time, I hung up the office phone, began cursing and told my boss to write me up if she didn’t like it; or later that week when a friend told me I sounded like “a single parent on the edge.”

One late afternoon, hurriedly driving to pick Mom up, I glanced at my face in the rear-view mirror. My eyes looked like my old man’s after an illness. Lines radiated everywhere. I flinched at what I saw.

That frightening image forced me to see the truth. At what point do you say to your mother: “I can’t take care of you anymore.”

I couldn’t.

Until she fell that last time.

She didn’t break anything, but she bruised herself and couldn’t walk for a while. The hospital sent her to a nursing home to recover.

Two days later, she was admitted to the hospital again, this time for dehydration.

I stood at the foot of her hospital bed and felt guilty looking at Mom’s small, sharp face peering outside the covers — teeth out, her mouth pinched and sunken like my father’s just before he died.

“This is what happens when you can’t take it and abandon your mom,” I thought.

I’m not sure when I realized that both Mom and I were better off if she didn’t come home. But she helped me make the decision.

****

One day, when she was almost finished with rehab, we talked about what to do next. She quietly told me it was time.

She fell in early November, and by December, she was living in the nursing home permanently.

Guilt and loss taste like sour milk; they smell like a dead skunk; they sound like a spoiled child’s scream; they feel like a jalapeño seed in your eye. That’s what it’s like leaving your mother in a nursing home.

It’s strange, visiting Mom in a place that I worked almost five years to prevent her from entering.

Sometimes I still wonder: Should I have kept her longer?

A nursing home is an institutional way station to the inevitable. You can visit often and make sure your mom is cared for.

But it can’t replace you. And I feel that nudge of guilt and loss each time I see her.

I feel the same emotions when I return to our empty house alone, each time I pass the closed door of her room.

I visit Mom every other day. Her anger has subsided into a wary optimism and a stoic handling of the inescapable. I get a kick out of how she lives for the little things, from a Hershey’s chocolate Kiss to the gift of a stuffed bear, from a game of bingo to a good night’s sleep.

It also helps me understand how little things work in my own life.

One night last week, my brother Perry called to ask if he could come over and sit on the porch and smoke a cigar.

It became two hours of conversation and laughter.

We both felt a muted desire for it not to end.