By Victor Greto

WEST CHESTER, Pa. — Even getting there is a state of mind.

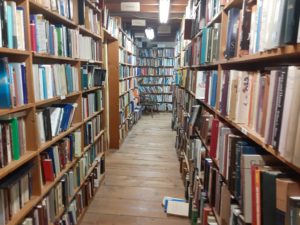

Baldwin’s Book Barn, five cobwebbed, creaking floors stacked with more than a quarter of a million books, sneaks up on you from the side of Lenape Road on Route 52 in the middle of a leafy, sinuous drive through the Brandywine Valley.

It may seem incongruous at first that the stolid barn, built in 1822 and set like a dusty jewel in the crown of the most gorgeous countryside in southeastern Pennsylvania, can gorge its wide-planked belly with this much of the past.

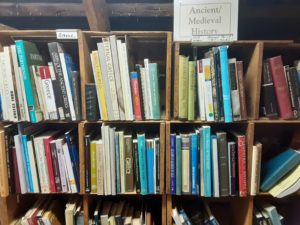

But the selected and collected works of the giants and not-so-giants of literature, history, science, philosophy and religion need no particular setting.

They just exist, many so full of time that, over the decades, they become timeless.

Like most great books, the barn itself is a refuge, a four-dimensional world where time and space weave themselves into a cozy womb that cradles both writer and reader as they engage in a conspiratorial whisper of point and counterpoint.

The dust on most of these books speak to the genius jumble of both loneliness and achievement, lightly cover an ambiguous world between sewn covers, tucked away and briefly forgotten on a shelf, aching to spread itself out and be known.

The wistful lines on bookstore owner Tom Baldwin’s face, perched behind a large wooden desk in an office that once processed milk, are a disguise. They actually point toward cool businessman’s eyes, flinty behind round eyeglasses, disinterested and slightly amused.

“I’m not a big reader,” says Baldwin, who inherited the business from his parents, William C. and Lilla H. Baldwin.

But he knows how to read the spines of books.

A look around his office shows the results of some of that reading: the collected works of Shakespeare, James Fenimore Cooper, William Makepeace Thackeray, Washington Irving, most in small editions able to fit into a gentleman’s waistcoat, one pocket over from the pouch that holds his pocket watch.

One doesn’t have to read very much to love readers, either.

“They’re the nicest people,” Baldwin says of them. “They always pay and their checks never bounce. I’ve never not gotten paid. It’s incredible.”

True. Women and men who brave the narrow staircases of the barn, where one sign warns them to “duck or grouse” as they go from floor to floor; who studiously ignore the flutter of wings up on the fourth floor by sociology and women’s issues — they do the “book thing” for the love of it, not the money, and they often are as conscientious as a schoolmarm.

Some are even as shy as Tom’s brother David who, tucked behind the biographies on the second floor, repairs damaged books.

“Every book is different,” David says, explaining away the better part of the ten years he’s been absorbed in this little pocket of the barn, healing the wounds created by readers and the passage of time.

At first, when asked how long he has been working here, Dave guesses, five, maybe six years. But brother Tom corrects him: “Ten years?” Dave says, looking at everything but your eyes, longing to return to the meaningful solitude of fixing the soft leather of an 1866 volume on American agriculture.

Every book may be different, but, like people, in their own company they begin to look and feel and smell all the same. The grainy feel, the moldy smell and the frayed look of neglected books leaning against one another for support are both heartbreaking and invigorating.

Which is part of the charm of perusing the barn. One browses as much to commune with the visceral nature of books.

Only about 20 percent of the store’s inventory turns over regularly, Baldwin says, leaving nearly 200,000 books to spend their days and nights pressed tightly or loosely against one another in the dark, for years.

But a century-old book has the potential passion of an unwieldy adolescent once it is opened.

Because you know, just like you know with people, that once you extract one from the crowd, away from the others, it magically comes alive.

Like Tom Baldwin himself.

His father opened his first book and print shop in Wilmington in 1934. They lived in a row home in West Chester, and Tom began toting his dad’s books around at the age of seven, earning 50 cents an hour.

After a World War II stint with the Navy, Dad bought the barn and the six acres that surrounded it in 1946. Abandoned for at least a decade, they fixed it up so they could both sell books and live in it.

“It was a gentle life,” Baldwin says, and not very remunerative. “You don’t get into the book business to get rich.”

But life is not all sweetness and light, and Baldwin left school in the eleventh grade to join the Marines. “I wasn’t a good student,” he says. But it was more than that, just like there’s more to the story of “The Great Gatsby” — a first edition of which Baldwin is trying to sell — than a tale about a rich guy who wants his old girlfriend back.

Baldwin’s father, who was friends with Andrew Wyeth and helped show his paintings; who made friends with several DuPonts; who bought and sold collections of books and helped found libraries, also was eccentric.

“I wanted to leave home,” Baldwin says.

Tom Baldwin made his own way, excelling at a number of jobs, from chef to car dealer to hotel manager, restaurant owner and innkeeper. He learned how to be a hard-as-nails businessman.

But in 1984, his father increasingly ill, Baldwin returned to the bookstore to help, and then officially took over the business after his father died in 1988.

Some of Baldwin’s fondest memories are of himself and his customers gathered around the pot-bellied stove near the entrance of the barn, passing the time of day discussing politics, history and philosophy.

“I looked forward to each day,” he says.

Then the Internet came and changed everything, he says.

Now, half his business is conducted online. A huge, flat computer screen dominates his large desk. After the Internet explosion of the mid-1990s, his business grew from employing a handful of people to more than two dozen full- and part-timers in 2000. Since then, it’s down to about 12 employees, he says.

The book business has become increasingly tough because a dealer is in competition with every other dealer around the world via e-Bay or Amazon.com. So Baldwin has had to act more like that hard-as-nails businessman he learned to become on his own.

The paradox of Baldwin’s Book Barn is that every dust mote and first edition reeks of the potential sentimentality of a boy’s or girl’s first reading, or an intellectual epiphany that changed their lives.

But there’s nothing sentimental about business, or Tom Baldwin.

Even so, the perfect book for the barn, as hidden as Poe’s purloined letter, slouches lazily against a copy of a work by David Hume, right there out in the open on a third floor shelf in the philosophy section: a dust-covered 1947 first edition of Herschel Baker’s “The Dignity of Man: Studies in the Persistence of an Idea.”

It just sounds right, for the whole place, for the whole point of books, the existence of the barn, even of Baldwin himself.

On the book’s frontispiece is a quotation: Plato having defined man to be a two-legged animal without feathers, Diogenes plucked a cock and brought it into the Academy, and said, “This is Plato’s man.” On which account this addition was made to the definition, “With broad flat nails.”

One also might add, “Whose checks never bounce.”