By Victor Greto

She didn’t like to cook, didn’t particularly like cleaning, and her brand-new husband didn’t want her to work.

All of 22 in 1973, Marcia Gallo was a stay-at-home housewife living in Levittown, Pa., a trademark middle class community that helped define postwar “normalcy” in American life.

She wouldn’t be doing it for very long.

“There was a parallel universe inside me,” says Wilmington’s Gallo, now 55 and a history professor at the Bronx Lehman College branch of the City University of New York.

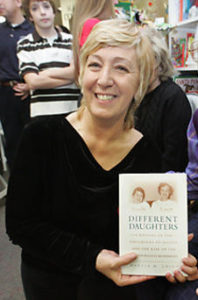

She is the author of “Different Daughters: A History of the Daughters of Bilitis and the Rise of the Lesbian Rights Movement” (Carroll & Graf, $25.95), a chronicle of the first organized lesbian-rights organization. Gallo places the movement as one of several groups in post-World War II America — including African Americans, heterosexual feminists and Latinos — who struggled for civil rights.

Gallo, born and raised in Wilmington, had been a typical “fun-loving” 1960s teenager, her friends and brothers say. Her room wallpapered with Beatles posters, she went steady with boys and loved going to the beach.

“We all had boyfriends,” says Debbie Palmer-Sutter, who attended Padua Academy with Gallo. “But she had the steadies. We were never serious. We were the smartest people we knew, and everyone wanted to be with her.”

And, like every other teenager, she had best friends with whom she incessantly talked and traded secrets, about boys and music and, later, Vietnam War-inspired politics.

Gallo could spend all day with her best friend Mary, says her brother Ed, “and as soon as she got home, she got on the phone with her.”

Her father grew so angry one time, he yanked the phone from the wall. “And that was the time when phones weren’t just plugged in,” Ed says.

Typical, even charming.

But during her teens, Gallo nursed an incipient political activism along with a healthy if ambivalent sexual appetite that would lead her away from Wilmington toward a life of social activism in California and an academic career in New York City.

Seeing herself as both a lesbian integrationist and a revolutionary, her work ultimately brought her back home, reconnecting her to her family, making friends and inspiring a small Wilmington lesbian community that she never even knew existed when she grew up.

****

Gallo speaks quickly and in a silky voice, leaning restlessly over a table while sitting in the home she recently bought from her aunt and uncle in the southwest section of Wilmington where she grew up.

She’s excited about a book signing later that afternoon at the Ninth Street Bookstore.

Owner Gemma Buckley promised two years ago that she would help Gallo promote the book she was writing.

“She came into our store as a customer,” Buckley says. “She said she was working on the book and wondered if I’d be interested in doing it as a signing. Definitely.”

In a way, her book signing will act as an official homecoming.

Although Gallo teaches in the Bronx, she commutes only once a week and stays there with a friend from Tuesday through Thursday.

She returns home to a place only two blocks from her 84-year-old mother. Her younger brothers, Ed Maggitti, a master electrician, and Mike Maggitti, a Wilmington police captain, also live nearby.

“This was my aunt and uncle’s home for 60 years,” Gallo says. “This house always had a good feel to it.”

Living and teaching fulltime in New York had grown to be exhausting, she says.

The clincher that brought her back home this past July, however, was that her partner of eight years, Anni Cammett, received a two-year fellowship to teach law at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

It is in Wilmington that Gallo is celebrating the publication of her book, a readable history of the first organized lesbian rights organization. The Daughters of Bilitis and its newsletter “The Ladder” arose in San Francisco in the mid-1950s and trailblazed their way into the late 1960s — until they were smothered by more radical lesbian groups and publications, including “Lesbian Tide,” “Gay Community News” and “Come Out!”

The book is the culmination of a half-decade of gathering information and writing, but it’s also the end product of a lifetime of figuring out who she is and how she wanted to live.

****

Gallo took to Levittown her subscriptions to Ms. Magazine and Ramparts, a left-wing magazine that ceased publication in 1975.

That counter-culture strand weaving itself around her thoughts was nothing new.

It goes back, she says, to her days at St. Peter’s Cathedral School on West 6th Street, where her racially- and ethnically-diverse fellow students gave her a widened perspective from her Italian-American neighborhood.

In 1963, Gallo’s seventh-grade teacher, Rosemary Brown, told students about her experience attending the March on Washington, where Martin Luther King Jr. proclaimed, “I Have a Dream”.

“It linked me to a larger world outside of myself,” she says.

But it was a link that failed to manifest itself until much later.

Being Beatle- and boy-crazy is nothing unusual for a teenage girl growing up in the 1960s. Nor was going to see the Beatles at Shea Stadium in 1965. Or spending chunks of summers in Wildwood, N.J., each year. Or cruising the parking lot at the Elsmere McDonald’s while a friend held a record player in her lap playing “Help!” and “You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away.”

It also wasn’t unusual to assume that she would not go to college, but would attend a business school to learn how to be a secretary like her mother. Gallo’s friend Debbie Palmer-Sutter studied with Gallo to be a secretary, and got a job with her at DuPont.

Even so, Gallo’s parallel universe grew.

“On our lunch hour we’d go to an anti-war protest at Rodney Square, and then go right back to work,” Palmer-Sutter says.

Gallo met her future husband, Victor, at Wildwood. He drove around in a very cool-looking GTO. She fell in love. “He was tall and cute and funny and Italian and worked in his dad’s construction business in Levittown,” she says.

He also was in the Army. In 1969, the year Gallo graduated high school, Victor was sent to Germany, and then on to Vietnam in 1970 and 1971.

When Victor got out of the Army in 1972, they had a long-distance relationship, and married in early 1973.

“I wanted to get married and have kids,” Gallo says. “But the reality wasn’t what the fantasy had been.”

It took them six months to figure out they were mismatched, she says.

During the marriage, she would come home to Wilmington for days at a time, much to the chagrin of her father, who would complain that he still was paying for the wedding.

Still married in 1974, Gallo got a job in nearby Newtown, Pa., as a secretary for Today Inc., a drug and rehabilitation clinic.

There, she began hobnobbing with “strong, independent women,” became involved in feminism, and joined the National Organization of Women.

Gallo even met an openly gay woman, with whom Gallo talked about the woman’s sexuality “as a curiosity.”

Later, a woman who had worked at the clinic got a job in California as head of the state’s drug and rehabilitation division, and asked Gallo to come out there to work.

After her divorce, Gallo did move, in 1977. Less than a year later, her career — and sexual orientation — changed.

****

Gallo never struggled with her identity, she says.

“An opportunity just presented itself, and after a long period of questioning things, the last taboo was removed.”

The woman she met and fell in love with was sexy. “I recognized the feelings of falling in love,” she says. “I may have ignored it in a different environment. But I was out of my usual environment.”

She’s never looked back.

“I don’t consider myself bisexual,” Gallo says. “I never had both relationships at the same time. When I fell in love with a woman, I stuck with that.”

And she’ll stick with that, she says, regardless of who she falls in love with in the future, man or woman.

Lesbianism as an ideology and identification transcends “gender” or how Gallo presents herself to the world, she says.

“I’ve been gay now longer than I was straight,” she says. “In my adult years, I have crafted a woman-centered life. I’m feminine, my presentation is as a traditional woman. But I’m a lesbian-feminist, and believe in women’s equality and the freedom to control our own bodies and love whom we want to love.”

Her position, however, is not anti-men.

“I also see lesbian-feminism as promoting human rights,” she says.

Gallo’s understanding speaks to the complexity of sexual orientation, gender and feminism, says Suzanne J. Cherrin, chair of the women’s studies department at the University of Delaware and an expert on feminism.

“Feminism has redefined itself many times over the years,” she says. “Recognizing lesbian rights and discrimination and how prejudice against lesbians is prejudice against women is crucial because gender is important in women’s success.”

Gender often becomes the sticking point in acceptance, Cherrin says.

“When you talk about gender, you’re often talking about social roles and stereotypes and behaviors, and there’s an umbrella of expectations for women,” she says. “Gender role expectations go into what works psychologically to convince people to be more accepting and tolerant.”

Gallo says she retains a traditional view of herself because it feels comfortable.

“We construct gender, it’s what society creates, and we either buy into it or we don’t,” she says. “I like wearing skirts, they’re comfortable. But I don’t feel constrained by my female gender identity. But many people do, and that’s why they play with it.”

That is, other lesbians project a “butch” or more masculine gender to the world.

The harder battle seems to be about accepting another person’s choice to be different, regardless of gender.

“I think people come to this place for different reasons and in different ways,” says Gallo’s partner Anni Cammett of lesbianism. “I prefer the company of women, and call myself gay. It’s shorthand for a lot of things: I’m interested in gay rights, and by affirming that, I’m making a political statement. If we were treated the same, maybe we wouldn’t have to say it.”

****

Gallo moved to San Francisco with her girlfriend in 1978, and found a job as a secretary for the American Civil Liberties Union.

Soon, however, she became a field organizer for the 25,000-member chapter there, and helped gear up voters to reject a law that would have banned gay topics and teachers from California’s public schools.

“Being a field organizer made me fully involved in civil rights and civil liberties,” Gallo says. She stayed in the job for more than 15 years, dealing with immigrant issues, fighting against the death penalty and domestic violence, and fighting for abortion rights and youth rights.

During her ACLU days, she met the aging pioneers of the lesbian-rights movement.

In 1955, they had founded an organization called the Daughters of Bilitis, named after a mythical woman who seduced Sappho, a historical ancient Greek known for her bisexuality.

After members of the group received an award from the ACLU in 1990, Gallo discovered that nothing had been written about them before.

“I couldn’t believe there was no book about this group,” she says. “They all were part of an ongoing struggle for civil rights in America.”

Gallo had been attending college courses piecemeal since her marriage, but put her education into high gear while living in northern California. She took courses at San Francisco State University and then Holy Names University, from which she graduated.

By the mid-1990s, Gallo had split with her previous partner and met another woman. She decided to move to New York City with her.

She began attending graduate school there at the City University of New York, and made telling the story of the Daughters of Bilitis the goal of her study.

She conducted dozens of interviews, including those with Wilmington residents Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen, a couple who figure prominently in the book.

For several years in the late 1950s, Gittings edited the organization’s publication, “The Ladder,” a breakthrough newsletter where lesbians first figuratively and then literally showed their faces to a wider public.

In the book, Gallo links the lesbian-rights movement with other civil rights movements of the time.

“Integration was what people were marching for in the 1950s,” Gallo says. “So it makes sense that the Daughters’ goal was to be accepted. They said, ‘We’re just like you except for who we love.’”

But in the late 1960s, the various civil rights movements fragmented.

“People began saying, ‘Do your own thing,’” Gallo says, “and the cry became I can be my own person. So gays and lesbians became about liberation, not conformist but revolutionary.”

Instead of sticking to the initial 1950s belief that lesbians should fight for the same rights as heterosexual women, what Gallo calls the mid-1970s emphasis on “the liberating power of difference” — such as incorporating the views of lesbian women of color, and the idea, championed by Gittings, that lesbians should ally themselves with gay men and not with straight women — fragmented the movement further.

That “need to engage multiple sites of struggle,” Gallo writes, “personal and political, energized some women but made others hunger for escape.”

****

When Gallo arrives at the Ninth Street Bookstore, there are happy shrieks as old friends and family trickle in.

Her two younger brothers, Ed and Mike, and their children; her mother, Grace, and old friend, Debbie Palmer-Sutter; the daughter of one of her best friends.

But there also is a contingent of people who want to hear her talk about the book, to meet the author and have her sign their copies.

“The lesbian and gay movement in many ways has achieved incredible things,” Gallo says later. “To go from the way the Daughters of Bilitis lived their lives, to the fact that we had a book party with the lights blazing, while 50 years ago, two women couldn’t dance together in a night club.”

Although only a handful of lesbian couples showed up under those bright lights, and according to some women attending the book signing, there are still few places to go in a city that has no “gayborhood” as in Philadelphia and other larger cities, most say a new openness has emerged.

For instance, a significant minority of high school and college women and men in the state have asserted their homosexuality by themselves or through organizations such as the University of Delaware’s “Haven,” a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and allies student group.

At the book signing, Gallo acknowledged both parts of herself.

“I came back here for family,” she says.

“We’ve shown the world new ways to construct a family,” she says to the lesbian couples clutching copies of her book.

Turning to her brothers and mother, she says, “But I also came back to the remarkable family I was born into. I am denying the old adage. I have come home.”