By Victor Greto

PIKE CREEK — Stanley Weintraub was born to write.

But not necessarily in English.

As a child, he had a rudimentary knowledge of Yiddish — a Medieval Germanic confection written with Hebrew letters and fashioned in central Europe — thanks to his grandmother, who taught him to read from a Yiddish newspaper.

But in 1935 at the age of six, he scrawled ETHOIPIA in block letters on the hardening cement of the front sidewalk of the Kaminskys, his neighbors across Percy Street in South Philadelphia.

The boychik’s misspelling of “Ethiopia,” referring to the Italy-Ethiopia War of 1935-1936 and inscribed for years in the pocked sidewalk, was one of the first signals that Weintraub’s destiny centered around both writing and history.

In English.

Like many of his generation, Weintraub was shaped by the effects of the Great Depression, which began during the year of his birth, and the continuing presence of wars around the world throughout the 1930s and 1940s.

Weintraub, 78, a retired Penn State professor, turned those dark and interesting times into a career.

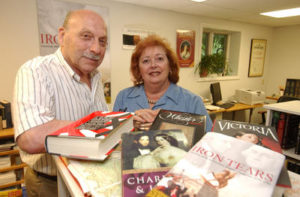

He just published his 52nd book, “15 Stars: Eisenhower, MacArthur, Marshall: Three Generals Who Saved the American Century” (Free Press, $30).

This, just seven months after the publication of his last book, “11 Days in December: Christmas at the Bulge, 1944,” which came out a short year after “Iron Tears: America’s Battle for Freedom, Britain’s Quagmire, 1775-1783.”

He’s working on two more books: a look at the American Civil War from the British perspective, and one about American expatriates living in Britain during the mid-19th-century.

“Some women have husbands who play golf, play poker, or run around with women,” says Rodelle Weintraub, his wife of 53 years. “Mine writes.”

Weintraub’s hobby, obsession — reason for being — squirms restlessly within the craft of writing books. Divided between military history and studies of the 19th-century Victorian era, his books not only refuse to slake a thirsty curiosity, but push him to research and write more.

“The important thing to know is that one book leads into another,” says Weintraub, sitting in the living room of his comfortably sprawling home filled with art from all over the world.

“Well, actually one book leads into many others.”

His books are lined on metal shelves in his basement office — rows of hard and paperback biographies, monographs, histories and literary criticism that have made him one of the most prolific modern writers of history and biography.

“He’s written about so many different things it’s hard not to run into him,” says Tim Murray, head of the University of Delaware’s special collections. “He always tells a good story.”

With only a little bit of stylistic massaging.

Weintraub’s Yiddish background put him into the habit of writing “with German construction,” says Rodelle, who also has written and edited several books, with and without her more prolific husband.

“I’m his editor and I’m harsh.”

Despite the wary — weary? — look he aims toward the Misses, Weintraub’s wry smile remains undaunted.

“She exaggerates,” he says. “Sometimes I put verbs at the end of (long) sentences,” as one does in German. “But it doesn’t happen often.”

Like everything else, those initial baroque sentences provide a lesson about writing.

“The first thing you want to do is get your ideas down,” Weintraub says. “Then you go back for style and repetition.”

****

Four years after Weintraub’s concretized misspelling, the 10-year-old boy began writing a history of the war via the afternoon and evening newspapers his parents got when World War II began with Germany’s invasion of Poland in the fall of 1939.

He took a lined copybook and began detailing the daily progress of the war gleaned from the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, the Inquirer and the Record.

Several copybooks later, he changed his mind.

“I was overwhelmed by the material,” he says. Not the facts, but the conflicting accounts, daily retractions and corrections the newspapers printed.

A year later, he fought scarlet fever, which put him in bed for six weeks. There, he continued to read newspapers and a book of Gilbert & Sullivan plays given to him as a gift.

Meanwhile, he had been collecting hundreds of bubble-gum war cards — if that doesn’t indicate the ubiquity of war during the 1930s, nothing does — and still has 300 of those colorful studies in patriotic propaganda.

The first book he took out with his first library card at the Philadelphia Public Library was journalist Hans von Kaltenborn’s book on the 1938 Munich Crisis.

This was a serious young man.

But you’d never have known it, says Charlotte Harris, a cousin, with whose family Weintraub and his younger brother stayed often during the summer in Marcus Hook, Pa., and in Arden.

“The two of them were imps,” Harris says of the Weintraub boys. “Little brats with gorgeous faces.”

Even so, Charlotte’s older brother put out a family newspaper whenever the family had their get-togethers in Arden. Charlotte’s father and Weintraub’s mother were brother and sister.

There was nothing scholarly about Weintraub then, she says.

“They were mischievous, the two of them,” Harris says. “He loved my mom’s hot dogs. It wasn’t till he got out of the service and went back to Penn State that the scholarliness came out.”

But it had been brewing.

One of Weintraub’s memories of Arden is as a 12-year-old sitting out on the grass one afternoon and listening to news reports of the Nazis invading Russia on June 22, 1941.

Weintraub wanted to write about history. He always wanted to write about history.

At South Philadelphia High School, he began writing short pieces about the various wars of the 1930s.

“I had grown up on the little wars before World War II,” he says. “The Spanish Civil War; the Japanese invasion of China; Italy and Ethiopia. The papers were always full of war.”

He attended West Chester State Teachers College, now West Chester University, and graduated in 1949 with a degree in education. He was only 20.

He had gone to summer school and finished in three years, commuting mornings beginning at 5:30 a.m. to get to a 8 a.m. class.

Working at a Center City wholesale neckwear shop as a clerk, and then behind the counter at a drugstore, he paid the $45-per-semester tuition.

He continued on to earn a Masters in English at Temple University, but not before being drafted to Korea in 1951.

In South Korea, Weintraub served as admissions officer for a prisoner of war hospital. He became a lieutenant, and earned a Bronze Star for “secret” work he conducted at the hospital: “turning prisoners” — convincing them to become spies for the American side.

“The whole program wasn’t very effective,” he says.

But he learned much more about the nature of war.

All human vices and virtues are magnified and accelerated during the crucible of war, Weintraub says.

“What came to interest me was why wars took place and how they were fought,” he says. “The cleverness and stupidity of them. The incompetence I saw — but, on the other hand, the courage and hard work.”

Exploring war became part of a vocation.

****

Exploring the Victorians became the other part.

To earn his doctorate in English at Penn State, which he attended after returning from the war, Weintraub needed a subject to write about.

“I knew George Bernard Shaw as a writer of plays,” he says. That was written about plenty. “So I decided to write a biography of Shaw as a failure as a novelist. That got me involved in the Victorian era.”

He never really left it.

From “Private Shaw, Public Shaw” in 1963, to “15 Stars,” Weintraub’s books graze over more than three centuries of military and English history.

They include Victorian-era biographies of English figures such as Queen Victoria, her husband Prince Albert, Edward VII, Benjamin Disraeli and T.E. Lawrence (of Arabia), as well as the American expatriate painter James Whistler.

His books on military history are among his most popular, and include “Silent Night: The Story of the World War I Christmas Truce,” “MacArthur’s War: Korea and the Undoing of an American Hero” and “The Last Great Victory: The End of World War II.”

Despite his in-depth trek through the horrors of the 20th century, Weintraub’s heart remains as much in 19th-century Britain, a period of energy and progress that saw, in the span of Queen Victoria’s life (1819-1901), the full flowering of the Industrial Revolution.

“Victoria as a girl saw the first steam locomotives,” Weintraub says. “Alexander Graham Bell demonstrated the phone for her. Automobiles were there during the last decade of her life. Two years after she died, the Wright Brothers flew the first airplane.”

Weintraub is enthralled with the acceleration of progress and the optimism it engendered.

He counts Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert — of “Prince Albert in a can” fame — as his “hero,” because of his sterling character, his championing of technology, and for inspiring the first world’s fair, in 1851.

But Weintraub is no Pollyanna.

The promising marriage of technology and optimism led to 1914 and the beginning of World War I, and the 20th century’s global wars, genocides and massacres. These events constitute the pessimistic underbelly of both Western Civilization and Weintraub’s interests.

The reason why Victorian optimism hit a wall in the 20th century, Weintraub argues, is because, “Technology outpaces human nature and we lose control of it.”

Human nature remains as selfish and mean as it continues to be generous and kind.

“Cautious optimist” that Weintraub is, “I keep hoping we change, and that education helps us change,” he says.

Even in the darkest days of war, Weintraub’s books invariably find a bracing measure of heroism and hope.

****

One can see Weintraub’s penchant for finding greatness and hope wrapped within the darkness of war clearly in “15 Stars,” which chronicles the intersecting lives of the three great five-star American generals of World War II — Douglas MacArthur, Dwight Eisenhower and George Marshall.

The culmination of a decade’s work — which included rooting through the three men’s archives and libraries — the book has a clear hero: Marshall.

“He’s the Prince Albert of this book,” Weintraub says. “He’s the one with ramrod integrity. How many people are in command of their own nature? It takes a lot of self-discipline.”

Unlike MacArthur, a vain, blustering drama queen; or even Eisenhower, the junior of the three who ended up with the most power — during the war as head of the Allies (thanks to Marshall), and then as a two-term President — Marshall’s stoicism, modesty and understated service during both world wars and within two presidential administrations argues for his greatness as both a war- and peace-maker.

It’s no surprise, perhaps, that Marshall happily ends his days nearly forgotten by the public, “mulching his garden.”

“I admire him for what he was able to do as a human being — the general who won the Nobel Prize for Peace” because of the famous “Marshall Plan,” that helped rebuild Europe after World War II.

“Peace,” Weintraub says, “is harder to make than war.”

Weintraub retired seven years ago from Penn State as Evan Pugh Professor Emeritus of Arts and Humanities. In 1982, he left an archive of his books and manuscripts at West Chester State University, his alma mater, called the Rodelle & Stanley Weintraub Research Institute.

The is no stopping Weintraub’s output because there can be no stopping the attempt to understand history. Like human nature, it resists a firm conclusion.

“What I want at the end of a narrative is resonance,” he says. “I don’t want someone to say, ‘That’s the way it is.’ I want some ambiguity.”